8 minutes

Using Vivado HLS on the Command Line

Introduction

Xilinx’s High Level Synthesis package, Vivado HLS, is an excellent tool for rapidly developing complex IP cores for FPGA designs. A relatively simple GUI and some reasonable support documents mean anybody can jump in and get started with the tool. However, more advanced users or simply those who have worked with the tool for professional FPGA development for just a few weeks will start to realise the limitations of the GUI. Fortunately the tool runs on a powerful underlying Tcl base which allows us to move to the command line to unleash the full power and performance of the tool.

Getting Started

Vivado HLS has a Tcl interface for scripting or interactive use on the command line. To use it you can just add arguments to the vivado_hls command used to launch the GUI.

To drop into an interactive session use:

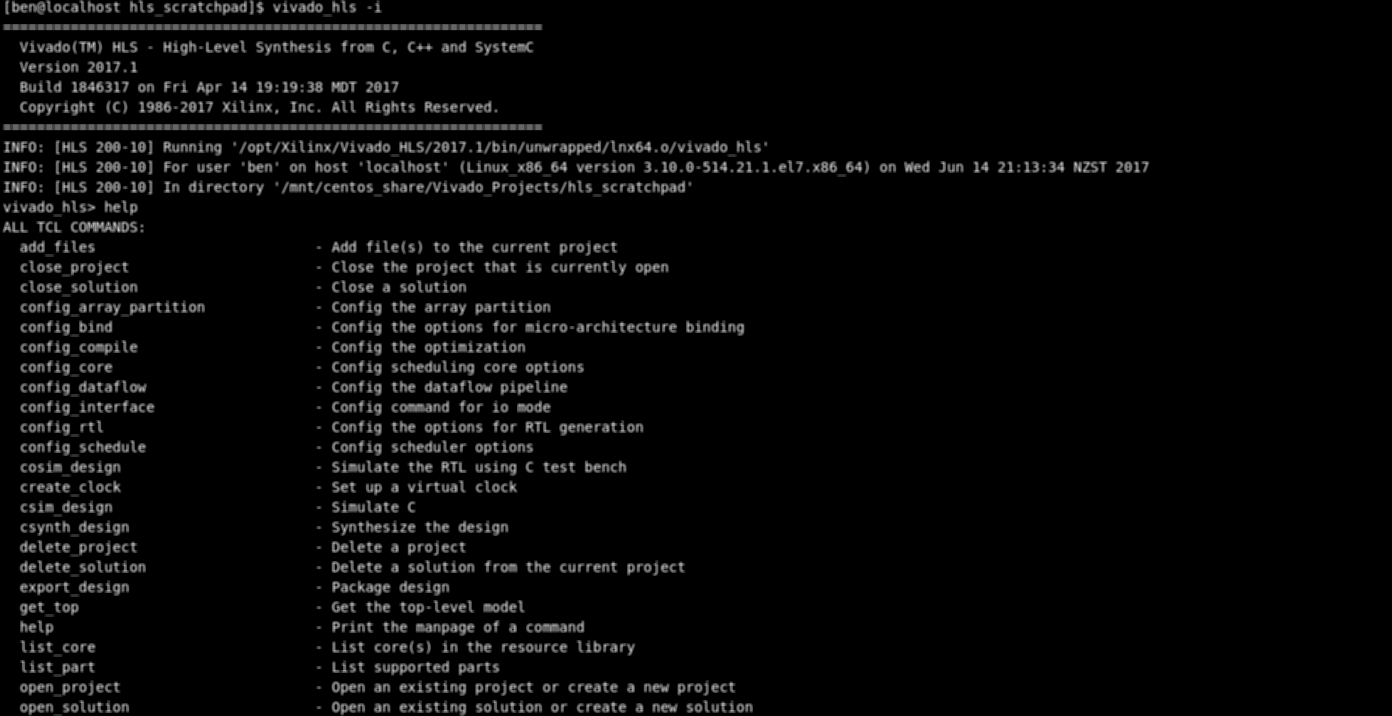

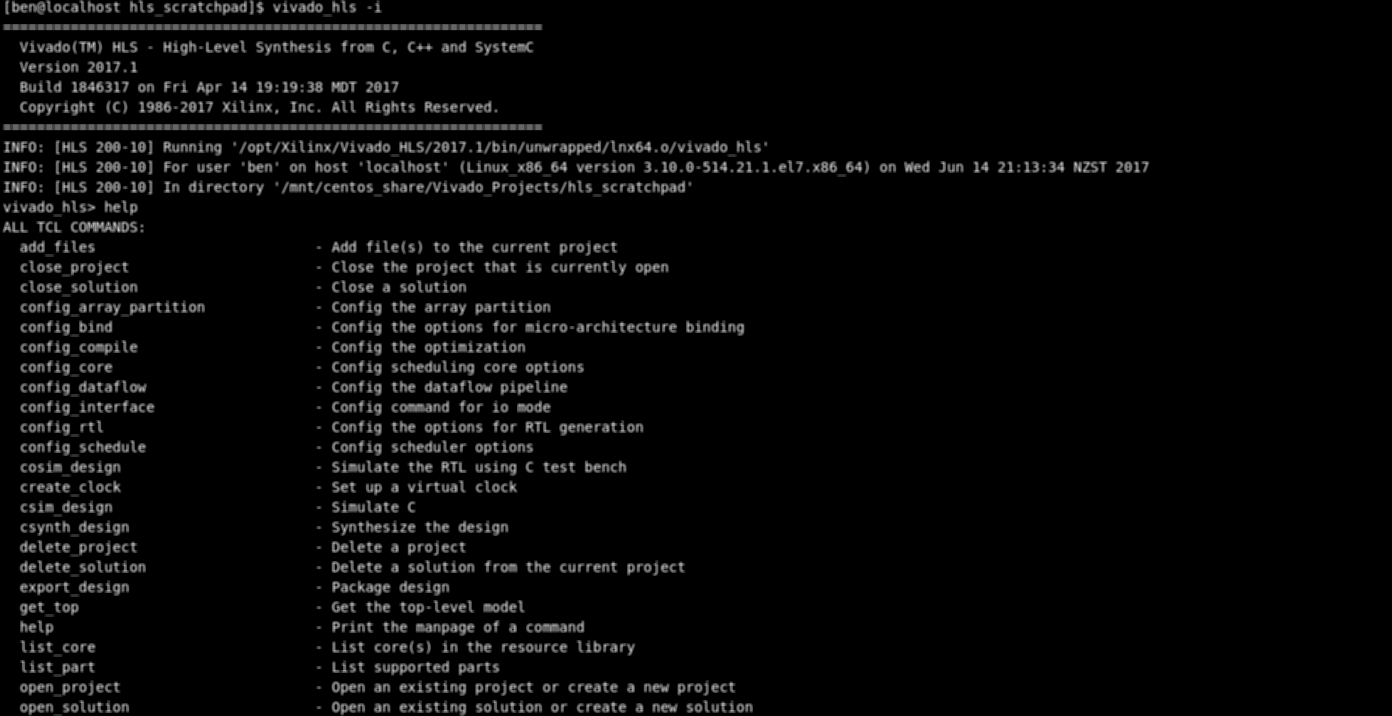

vivado_hls -i

Or to execute a scripted batch run use:

vivado_hls -f script.tcl

Once in the interactive environment you can use the help command to list all the commands available and drill down into more detailed help info on each individual command.

For most simple projects the interactive workflow would look very familiar:

- Open a new/existing project.

- Open a new/existing solution.

- Define a device.

- Define some source files.

- Specify a top level function for synthesis.

- Optionally, define some directives.

- Execute one or more of the build phases (c simulation, synthesis, cosim, etc).

And then probably iterate around modifying your source/directives and running builds.

Once you have an optimised solution with a build process you are happy with then you can add the commands you need into a Tcl script and move to a scripted build process.

Performance

One of the big advantages of working on the command line is the gain in performance of the tool. The underlying HLS processes are free to run at improved speeds because fewer overheads are required to maintain the GUI, open and close reports as they are generated and replaced, and capture and present every log message as it happens. Beyond raw processing speed I would also suggest that once adapted to working with the tool’s command line environment then the reduction in time spent clicking around in what is often (at least on Linux) a frustratingly laggy GUI, also offers a significant improvement in productivity!

To explore these claims in a better way than just collecting anecdotal evidence I put together a rather un-scientific test to compare the execution times of the 3 most common HLS build processes: C simulation, C synthesis and cosimulation.

The test design used was a quickly knocked together floating point implementation of a sin function which uses a Taylor Series approximation. Xilinx offers a sin/cos function as part of the HLS math libraries but writing one out offered the chance to compare build performance at a couple of different stages of the design process. I used a basic stopwatch test to time the execution of the 3 build stages first using the GUI and then using a Tcl script to invoke the equivalent command. The stopwatch was started when I clicked the last button in the GUI before the process starts (which was the dialog box’s ok button for both C sim and cosim) or when I hit return after issuing the vivado_hls -f script.tcl command. The stopwatch was stopped as soon as the final line of the process was printed. I gave each tool 3 runs of each build stage to generate an average. Raw data for the results can be here.

| Partially Optimised Results | Fully Optimised Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Command Line (s) | HLS GUI (s) | Command Line (s) | HLS GUI (s) | |

| C Simulation | 2.65 | 4.50 | 2.52 | 4.56 |

| C Synthesis | 7.51 | 11.59 | 8.06 | 11.22 |

| Cosimulation | 120.79 | 1305.41 | 114.92 | 116.37 |

HLS Execution Times

It should be reasonably obvious that the general trend of these results backs up my claim of better raw tool performance from the command line interface. What’s really startling is the cosimulation results for the partially optimized design; a nearly 10x difference just by not using the GUI. This appears to be down to the level of output from the simulator and is something I’ve noticed time and time again working with HLS. If your HDL simulation, for whatever reason, outputs a lot of INFOs or WARNINGs (which is very common with generated code) then the HLS GUI seems to grind almost to a halt. In fact, whilst generating that particular group of results I had several full hangs of the cosimulation process. Anecdotal evidence would suggest that performing the same simulations using the Tcl interface has never shown this to cause the same issues, something it now looks like I can back up with an example.

The code used for this experiment is on [Github](“https://github.com/benjmarshall/hls_scratchpad/tree/master/hls_cmd_line_testing") along with the full solution folders for the fully optimised design (I’ve left some comments in the code if you want to manually roll back to the ‘partially optimised’ version). This is a small design suitable for a good basic test, but in my experience the same trend holds true (and gets worse for the GUI) as a design becomes more complex and the build/simulation times increase.

Source Control

Not much information exists on how to manage Vivado HLS projects under source control. Xilinx have tried to disseminate some information about the Vivado approach to revision control, but this focuses on the main Vivado tool and how IP cores are managed once they exist with the IP catalog. How do we manage the source for a Vivado HLS project?

One of the big issues with managing Vivado HLS projects is the amount of files found within a typical project directory. Most of these are generated by HLS. In fact, only the raw source code files are not generated by the tool in some way. As a general rule of thumb I would suggest it is good practice to avoid putting generated files under source control. However, the current status of the project: which build phases have been run, the source file locations, report locations etc, are all wrapped up in some generated ‘project files’. In order to avoid re-creating the entire project structure each time we want to ‘check in’ or ‘commit’ some source changes we would have to store these generated files with our source code. This creates some rather large commits to your source control tool, and will lead to a lot of file deletions, creations, and replacements on every subsequent commit. Messy!

Taking the GUI out of the equation and moving to command line driven development approach eliminates almost all of these concerns. If a Tcl script is used to control the build procedure then everything to be placed under source control is plain text and exclusively user managed. The Tcl script defines everything needed: the project name, source files, top level function, device, clocks, build procedure etc. If we simply store the raw source code and a single Tcl script then we know, regardless of which project we are pulling (or building, or anything else), that we can re-create the previous build results by executing:

vivado_hls -f script.tcl

Simple!

Drawbacks

As with everything in life, not everything about switching to the Vivado HLS Tcl interface is a positive. Firstly you lose the GUI, it may seem obvious but it’s worth talking about some of the more interesting drawbacks this has. We lose access to the code highlighting and tooltips which can aid development, you know that red squiggle that means you typed a function name in wrong, or you haven’t included the correct header file. You lose the ability to easily explore the built in HLS classes and functions by ctrl-clicking on types or function names. You also lose the ability to use the dataflow and analysis view, which can at times prove extremely useful for optimising a design.

The second major item on the drawbacks list is the Tcl interface itself; it’s quite clunky. The commands aren’t the easiest to remember, they aren’t that short, and many of them have arguments that you end up wishing would be on by default to avoid having to type them out every damn time!

Summary

In summary, the Vivado HLS Tcl interface offers a performance increase for demanding builds, and I would argue that on balance avoiding the laggy (and frequently buggy) GUI speeds up design iteration. Embracing a command line driven approach naturally leads to an easy scripted build process and a much easier time with source control. I have personally used both SVN and GIT for professional and personal projects using a primarily command line driven design process.

Avoiding the GUI outright does introduce some major cons though, we lose some of the useful code editing features and the neat optimisation tools. The obvious conclusion is that a productive design process should take a balanced approach. I often start development of a HLS project in the GUI as I architect my code and iterate over the first few C simulations to ensure correct functionality. However, as the design progresses towards the optimisation phase and I start iterating through C synthesis and cosimulations rapidly, I move almost exclusively to the command line using a Tcl script to drive the tool. The exception to this rule is when I need access to the optimisations views, fortunately launching the GUI and opening the generated project is easy and provides access to all those useful features without removing the benefits of returning to the command line for the next build.

I’ll follow this post up soon with a more detailed run through of my current design process for working with Vivado HLS. Until then, give the HLS Tcl interface a go if you’re not using it already, you won’t regret it!